"Brooklyn Flea",

"Brooklyn",

"Cards",

"Javits Center",

"National Stationery Show",

"New York",

"Poland",

"Stationery",

"card",

"etsy",

"etsyny",

"governors island",

"greeting card",

"letterpress",

"note card",

"pepper press",

"printing",

"tella press"

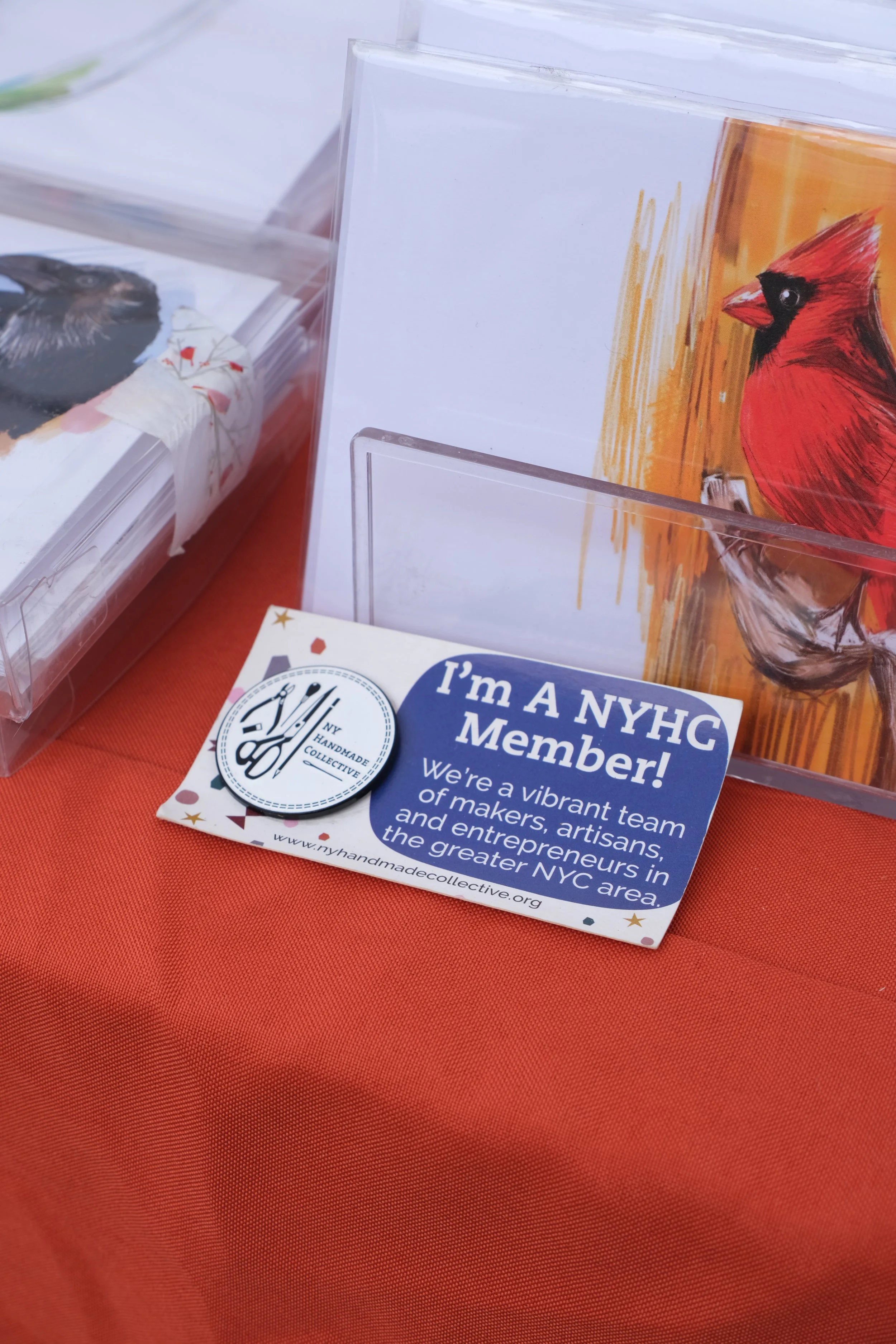

NY Handmade Collective

"Brooklyn Flea",

"Brooklyn",

"Cards",

"Javits Center",

"National Stationery Show",

"New York",

"Poland",

"Stationery",

"card",

"etsy",

"etsyny",

"governors island",

"greeting card",

"letterpress",

"note card",

"pepper press",

"printing",

"tella press"

NY Handmade Collective

Read More